Chapters Dialogue/Project/Implementation/de

The implementation of the projectVerstehenTo enable Kira to carry out a deep-dive into the complexity of the Wikimedia universe, Nicole prepared a collection of documents, links and stories, held long monologues and put Kira in touch with long-standing Wikimedians and colleagues at Wikimedia Deutschland. Fortunately, the Chapters Dialogue project could take advantage of a large amount of data that was already there. Kira dug into various data sources and collected input, questions and topics. Having a huge pool of contacts, information and documents is crucial at this stage, and was a basis for Nicole and Kira to use to create an extensive questionnaire that would cover all topics we wanted to focus on in the research. We also decided that we needed different questionnaires for Chapters and Stakeholders in order to ensure different roles and perspectives were accurately surveyed. It took some drafts and feedback-loops until we got the first version and were ready to start the interviews. Kira conducted the first interviews with stakeholders (one representative each from WMF and the Affiliations Committee) and fours Chapters (Wikimedia Australia, Estonia, South Africa and Taiwan) at Wikimania in Hong Kong in August 2013. We improved the research questions based on the feedback we gathered during our kick-off session at Wikimania, the first interviews and several one-on-one conversations. Beobachten The heart of the project was the actual interviews: Kira interviewed volunteers and staff from Wikimedia Chapters, the Wikimedia Foundation, the FDC and the AffCom in order to find out what matters to each of them. To make this possible it was necessary

Throughout the project, we needed to adjust the "tourdates" according to the availability of interviewees, the complexity of the matter itself, or other unexpected events. Professional and reliable administration is the backbone of a project with such a scope. The support and participation of volunteers and staff at WMDE, WMF and participating entities enabled us to handle the logistics within the tight timeline. We experienced great hospitality and commitment from all over the world. Kira had to travel many miles in the course of the research. She needed to adjust to time-zones, languages, climate and cultural habits, convince airport security that her sound recorder was not a weapon, until she finally reached the destination: meeting her interviewees face to face. It was quite an adventure, and the interviews took place in all sorts of locations: offices, hotel lobbies, cafés, restaurants, by night on the Zócalo in Mexico City, during train rides and even on pyramids. Evidence can be found in the Chapters Dialogue Facebook stream.

While an official interview lasted around 90 minutes, we always tried to spend some extra time with the interviewees, in their office with the rest of the team, at lunch or dinner or during a stroll through their hometown. This extra time was of significant importance, as many interesting aspects were revealed after the official interview was over – sometimes really the very minute after the sound recorder was switched off. During casual talk people tend to open up and provide either additional information that deepens the understanding of their story or even new and sometimes surprising aspects that didn’t come up during the interview at all. In addition, people who were not official interviewees had the chance to tell their version of the narrative. Even the smallest remark was sometimes really useful and uncovered valuable insights. For organisational reasons, some of the interviews were done via video conferencing. Even if we knew that a conference call would not deliver the same quality as a face-to-face interview, in some cases it was unavoidable. Our caution was confirmed: especially when meeting for the first time, a conference call can be a bit awkward (socially and technically). It is hard to create an atmosphere of trust, and it does not allow for extra “unofficial” time that is so valuable for the interviews. We therefore limited the number of video conferencing interviews to a minimum, but were glad that this gave us the chance to have additional and – nevertheless – valuable conversations. Either way, Kira worked through the travel and interview schedule and dug deep into the trials and tribulations of the Wikimedia universe. Countless notebooks (paper ones!) were filled, new questions arose, hundreds of topics were discussed, and the quantity of stories grew steadily. Between September 2013 and March 2014, she had collected personal stories from 94 individuals. Iteration and participationA very important aspect of Design Thinking is its iterative character. Everything from tools to ideas and prototypes can and should be adjusted or completely changed based on what is learned during the process. This approach fitted very well with the openness of the Wikimedia movement and the working culture at Wikimedia Deutschland. It provided the Chapters Dialogue team with a lot of flexibility and enabled us to iterate the research design and steadily improve its quality. We wanted to conduct the research project in an open and transparent way, calling on all the Chapters and interested people for active participation. Iteration meant for us:

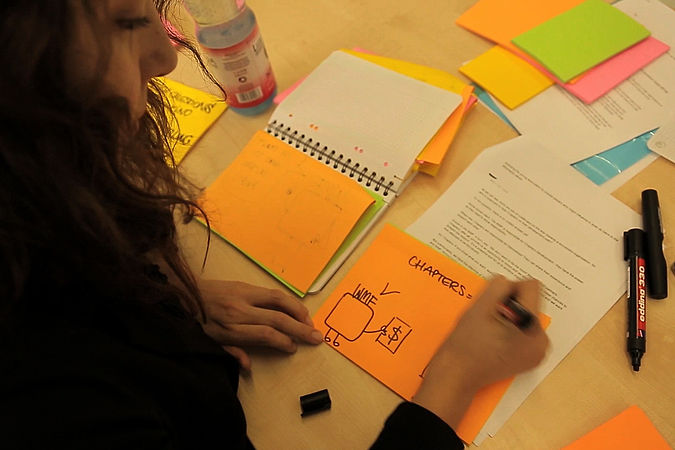

Instead of just setting up Meta pages and getting lost in endless mailing list discussions we went for a coordinated and structured approach. Staying flexible, adjusting throughout the process and allowing participation were the keys for this project smoothly and successfully running in a professional way. SynthesisThe synthesis was the trickiest part of the project. The amount of data and information we gathered in the research phase was huge. From March until the final presentation on 11 April 2014, Kira documented the key statements and background stories from the interviews in hand-written notes, we audio recorded almost all interviews (subject to the approval of the interviewees) and had them transcribed. But how to make sense of all that data? How were we to find commonalities and differences? And finally, how were we to create an understandable yet comprehensive summary of it all? The art of synthesis lies in paying attention to details and interesting quotes, but keeping the whole picture in mind at the same time. The various stories needed to be condensed into one narrative that could be told to the movement. Our goal was to mirror the movement, to present the whole picture of what it actually is, what people care about and where the trouble spots are. For the synthesis of a large amount of information, a visual process is of paramount importance. Mapping information visually enables an overview of a complex topic to be obtained which is very much harder to get by just reading hundreds of pages of written text. Information can be processed more easily when it can be seen at a glance, bits of information on sticky notes can be rearranged, clusters can be created and coherences of different topics can be identified. Having information presented visually also permits it to be shared with people who are less involved, and for feedback to be received, information to be restructured and everything to be grouped in one spot. Co-creation was crucial for this project, as several brains were needed to process and digest all the information.  The visual process is supported by the extensive use of sticky notes notes in order to “extend one’s own brain” onto walls, windows and whiteboards. The content needed space to develop, interconnect and grow. It was impossible to map it all at one desk. Wikimedia Deutschland’s spacious office and the cooperative WMDE staff provided the perfect conditions: we were able to work in a huge and bright room that not only provided space for sticky notes, but also for thoughts, action and creativity. After setting the scene, the actual work could begin: we shuffled the information a hundred times – that’s where the flexibility of the sticky notes and whiteboards paid off – and looked at it from all possible angles. We tried to distil the key issues and bring order and clarity into the mass of information. It was a process of building an understanding, of learning, of challenging assumptions, of finding and losing the common thread. It took a good chunk of time, countless discussions and iterations to bring clarity into the “creative chaos”. As a preparation for the final presentation, we took the chance to present a preview of the insights during the Chapters’ Executive Directors’ retreat (February 2014, Berlin) and the Board Training Workshop in London (March 2014). Final presentation The Wikimedia Conference (April 2014, Berlin) provided the perfect setting for our final presentation (60 mins, ~120 people in the audience). All the work from the previous nine months culminated there. The Chapters Dialogue was all about stories and so was the presentation. Rather than using presentation slides, we decided to tell the story with the same tools we used for the synthesis: whiteboards and sticky notes. This allowed the audience to witness the creation of the story, to keep track of the bigger picture and to use the material to relate subsequent discussions to it. The big advantage of the flexible setting was that it does not look as if it was cast in stone, as if people could not disagree with it and build upon it. Half of the people in the audience indicated that they had been interviewed in the course of the project. The feedback after the presentation was overwhelming, and discussions in the following days often related to this presentation. While one of our main goals for the project and the presentation was to point to the “elephant in the room” and enable people to finally realise and talk openly about the trouble spots within the movement, several people expected very concrete and detailed solutions. We refrained from presenting recommendations for concrete action because we think more analysis, consultation and cooperative approaches are required. We ended the presentation with six tough questions, that the movement urgently needs to address in a structured and coordinated way. DokumentationThe documentation (written report, short movie) took us way longer than expected. Only the glorious team work of Madame “I know the perfect phrasing for EVERYTHING” Ebber, Miss “Tarzan in the insights jungle” Krämer and Mister “Knight in shining armor” Kibelka made the publication of this document possible in August 2014. |

Go to the next chapter

and learn more about Or go back to know more about

|