Fundraising/Chapters/WMDE 2014 Report

Executive Summary

[edit]Fundraising at Wikimedia Deutschland, and across the entire Wikimedia movement, not only helps us achieve financial goals, it also helps raise awareness for our mission. We reach several million people each day during our fundraising campaign in Germany, making ours the most successful online campaign in the country. With the help of a systematic strategy and comprehensive A/B tests, we have managed to increase our annual fundraising campaign revenue by more than ten times in just five years. This success is the result of a data-driven approach that focuses primarily on donors and their behavior.

This Fundraising Report reviews the findings gathered from our latest campaign and assesses how our work has developed over recent years. Thanks to extensive A/B tests and the technical infrastructure that we have built up over the years, we are constantly and systematically collecting data and insights. This allows us to analyze the behavior and payment methods of donors, which in turn helps us to plan and continually improve our campaigns. We have identified five main factors that contribute towards fundraising success at Wikimedia Deutschland, and this report discusses them in detail.

1. Relevance: No association, no donation. Our results show that a personal appeal in banners, the use of key words, and particularly references to current events make our appeals more relevant and therefore more persuasive to potential donors.

2. Visibility is something one has to fight hard for. The time span we have in which to draw attention to our message is very short. This Fundraising Report presents findings relating to when is the best time for the banner to appear and analyzes various design decisions, including color scheme.

3. Closer to the reader: If there is one thing that the entire donation process should be–from reading the appeal through to completing a donation – it’s straightforward. The fewer clicks required, the better. This fact is nothing new, and it certainly does not only apply to us, but this report will explain the concrete application of this knowledge in the creation of successful banners.

4. Donation obstacles should be kept to a minimum. Two findings in particular have emerged from our previous years’ work: Firstly, including suggested donation amounts on the banner has proven to provide effective guidance for donors. The lower the sum, the higher the number of people who donate–and the overall success of a campaign is greater when more donors give smaller amounts. Secondly, the option to donate anonymously is very important to many donors.

5. Raising the campaign profile: It pays to communicate fundraising goals and show the progress of donations. In 2014 in particular we saw how effective the creation of dramatic moments within a campaign can be. This report also touches on a surprising topic: the principle of “social proof” demonstrates how the behavior of a group can motivate others to act in the same way, yet Wikimedia Deutschland’s fundraising campaign made good use of the reverse of this effect.

Looking back, the five factors all played a crucial role in the success of our campaigns; and looking ahead, their importance for the international movement stretches far beyond monetary matters. We should all see fundraising as the start of a relationship – one that requires continuous care and attention.

Our goal for the future is to persuade donors to become long-term supporters of free knowledge and the Wikimedia movement. This report provides a glimpse into our strategy on how to maintain and consolidate our donor relationships, which are built on three main pillars: regular contact, targeted appeals, and personal dialogue–all things that are not possible through communication via banners alone. This report discusses the enormous benefits that stand to be gained from attracting long-term support for the Wikimedia mission.

Using the example of donation certificates, this report will show how we benefit from taking the wishes and expectations of donors seriously. Our postal and electronic mailings are proof of how target-group-specific content and communication strategies can ensure long-term success. The fundamental importance of a well-functioning customer service team should also not be overlooked. During the last fundraising campaign in Germany, for example, we received hundreds of calls and answered well in excess of 5,000 e-mails. Contact is therefore not merely an additional service; it is the very basis of future relationships.

Looking ahead to future challenges, the report ends with a call to intensify donor relationships, to focus on donors’ needs, and to further diversify fundraising communications.

Introduction

[edit]Wikimedia Deutschland has been running professional fundraising campaigns since 2010. In previous years, all fundraising was undertaken by volunteers. With the creation of the non-profit Wikimedia Fördergesellschaft (WMFG) in 2011, we now have the institutional requirements in place to forward all donations received in Germany to the Wikimedia Foundation and Wikimedia Deutschland. At the heart of our fundraising activities is the big campaign that we run at the end of each year, but sending out e-mails and postal mailings also constitutes a large part of our work. Over the years, our fundraising activities for Wikimedia have brought us extensive knowledge and experiences. The many A/B tests that we have been carrying out systematically in Germany since 2012 have been particularly helpful in this regard. We have also learned a great deal through our donor surveys, and every enquiry made about donations, either via e-mail or telephone, gives us feedback on our work – feedback that is crucial for improving our fundraising strategies and establishing good relationships with our donors.

This report should give readers insight into how we organize and implement our fundraising campaigns in Germany. It is intended to provide not only the figures, but also the story behind those figures. Thanks to our many years’ experience as fundraisers, we have been able to identify certain factors that play a major role in ensuring a campaign’s success. We have also developed effective means of gaining long-term support for our mission by forming lasting relationships with our donors. This report is intended to paint a detailed picture of all the most important insights gained from recent years.

Fundraising facts and figures

[edit]Fundraising for Wikimedia is an exciting and unique challenge. We are raising money for a project that people use on a daily basis and are therefore personally invested in. So, unlike most other fundraising-driven organizations, Wikimedia’s fundraising activities do not simply target people’s charitable nature; our project provides a concrete personal benefit to every single donor: free access to knowledge.

We reach millions of people every day during our annual fundraising campaign – our donation banner is loaded up to 20 million times a day in Germany. This wide reach is indicative of a very comfortable situation, and is one of the main reason behind the huge success the fundraising drives have experienced since they were first launched professionally in Germany by us in 2010. Currently, we run by far the most successful online fundraising campaign in the country.

But despite our success, we still have much to accomplish. Even though our banner was seen at an average of over 13 million times a day during the last fundraising campaign, less than one percent of those who viewed it actually made a donation. So how can we utilize the enormous potential of the other 99 percent? Why are these people not donating, even though Wikipedia probably plays an important role in their daily lives? These are the questions that lie at the heart of our day-to-day activities.

Where our donations come from?

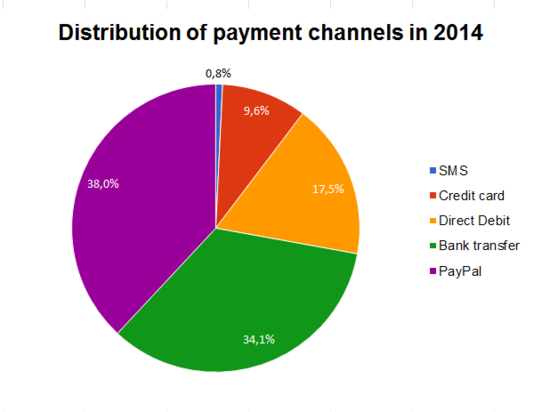

We offer five different payment options for making donations: SEPA direct debit, bank transfer, PayPal, credit card, and SMS donation. Since the last fundraising campaign, we have also introduced Bitcoin as a payment option, but due to its low revenue (around €1,500), it is not yet relevant. In recent years, PayPal has become an increasingly popular means of payment, while donations via direct debit have dwindled in popularity. A slight increase can also be observed in payments via bank transfer, meaning that three out of four donors now make their payments via bank transfer or PayPal.

Looking at the distribution of revenue sources, it is clear that the vast majority of donations are made via the banner on de.wikipedia.org. Donation banners on the mobile website and at wikipedia.de (Wikimedia Deutschland search portal for Wikipedia) as well as campaign-related e-mails have not yet managed to generate donations on a similar scale. Last year, the only other source that made a signification contribution to the total donated sum of €8.2 million was our postal mailings (up to €1,400,000). However, the problem here is that these donations cannot be tracked perfectly. We are able to trace €400,000 directly back to postal mailings, but the total revenue indirectly generated by these mailings is likely to be much higher. Database analyses show that postal mailing recipients donated a total of €1,400,000 – including online donations via banners. We cannot reliably determine from these data what precisely motivated these donors, but it is very likely that our postal campaign had a reinforcing effect.

A/B-testing at Wikimedia Deutschland

[edit]Although donating to non-profit organizations is less widespread in Germany than it is in the Anglosphere (see World Giving Index 2014), we still succeed in convincing more and more people to donate to Wikipedia every year. This success is largely thanks to our extensive A/B tests, which we use to optimize our banners and donation pages. We have been conducting series of A/B tests for four years now – not only on the desktop version of Wikipedia, but also on the mobile site, the wikipedia.de search portal, and via postal and electronic mailings. These tests are based on assumptions about user behavior and the effects of the design, function and message of the banners. Over time, this has allowed us to identify specific success factors, which has contributed significantly to an increase in revenue.These five factors shall be described below. Before, we share some details about our technical and methodological basis of testing.

A central requirement of a campaign test is the clarity of the concept. As a rule, we usually test one element at a time. This is the only way to determine the direct impact of changing certain variables. Such a methodical testing method is painstaking, but it is vital if we are to clearly identify the factors that lead to better communication.

Having implemented the necessary technical infrastructure, we now have the ideal framework in place for carrying out reliable A/B tests and analyzing the results. Over the last four campaigns we have carried out hundreds of these tests.

In recent years, we have programmed database modules to allow for the immediate analysis of these tests. As can be seen from the screenshot below, we automatically record the most important metrics – such as donation per page view and donation per visit to donation site – and then the program calculates the percentage deviation between the test group and the control group. In addition, a statistical significance test provides information on the reliability of these results.

To ensure meaningful results, the first prerequisite is a large enough sample, i.e. a minimum number of donations per variant (usually around 1,000 donations). But even once this number has been reached, we must decide how high a deviation needs to be before it is given credence. When analyzing A/B tests, our focus is always on the statistical significance of a deviation (chi-squared test). Our analysis software can even create visual representations of the temporal development of the corresponding statistical parameters (as well as all other metrics). This has enabled us to see time and again that the analysis metrics and significance values can be subject to considerable fluctuations, teaching us that tests should always be carried out over as long a period of time as possible – ideally for several days. After all, user behavior and the user base differ between weekdays and the weekend and also depend on the time of day. In addition to ensuring appropriate test length, we carry out test repeats to check the validity of results and increase the reliability of our findings. After all, these have a direct financial impact.

Given the financial importance of test interpretations for the length of a fundraising campaign and the need to achieve our daily targets, fast and targeted analysis is essential. The presence of a comprehensive analysis tool allows us to assess the relevant metrics while the test is still up and running. With the help of automation tools, we can also always keep an eye on other A/B tests running simultaneously and react accordingly. Our analysis software also provides a number of essential figures and graphics that allow us to fully assess and control the general progress of the campaign.

Success factors for banners

[edit]Over the years, we have conducted a variety of banner tests and have tried to systemize our results. In the past, our approach to designing banners was based on a number of very different concepts, and we have learned a lot from our successes and failures. We are now able to identify five success factors for effective banners. Of course, these factors are not exhaustive and they are mutually dependent. Successful banner communication is therefore not just the result of individual success factors, but rather the result of interaction between the various factors at play.

Relevance

[edit]It may seem obvious, but Wikimedia fundraisers have to point it out time and again: very few users visit Wikipedia to donate. People visit Wikipedia to get specific information as quickly as possible or to quench their thirst for knowledge. For users, all the messages that come up in addition to their specific searches are initially of secondary importance, and may even be irritating. We might therefore assume that such messages are often not noticed at all. User behavior on the Internet is very much shaped by people tuning out messages and advertisements. In principal, this also dictates whether or not they take notice of our donation banners. Ideally, we should fall into line with the donors’ original reasons for visiting the site. But when are Wikipedia users receptive to other stimuli and messages and how can we ensure we get the necessary attention?

People can support Wikipedia by making a donation all year round. The navigation toolbar on the left-hand side contains a donation link, but very few people ever click it. It is clear that users need to be convinced, first and foremost, to donate money to us. But given that people’s attention span on the Internet is generally very short and that there are only a few seconds for us to communicate a message, choosing the right form and content for that message is of great importance.

A short while ago, we worked almost exclusively with a personal appeal from Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales. In Germany, Jimmy’s appeal was eventually combined with very effective messages from German Wikipedia authors and Wikimedia Deutschland employees. We now no longer launch personal appeals and only use the so-called facts banner.

The facts banner, which contains significantly less text, communicates the most important facts about why we need donations on the very narrow space offered by a banner. Following a series of tests, we were able to identify what content is relevant to German users.

We found out that, in Germany, a polite tone is very important. We therefore address Wikipedia users formally and apologize for any inconvenience caused. By mentioning that we only ask for donations once a year, we are able to make the appeal particularly unobtrusive. That way, an appeal for donations is justified at that specific point in time.

The relevance of the message is very important for people’s decisions on what information they choose to take in. Who is speaking to me and why? People ask themselves that question daily when surfing the Internet, so, on Wikipedia too, we need to make our message relevant to the user. For this reason, the text in the banner is written as a kind of letter, with a form of address at the start and a closing formula at the end. It is thus clear that the website operators are addressing the reader directly. In this way, the message itself becomes more personal and the appeal significantly more credible and trustworthy.

Relevance to the reader is established by including topical and personal content. The effectiveness of a message suffers if it is communicated without context or relevance to the recipient. We therefore seek to personalize the message for the reader as much as possible. A useful thing to do is to name the country in which the user is based (e.g. “Now we are asking you in Germany to help out”, 11 percent increase) and to (automatically) include the exact day of the week (e.g. “on this sunday” - 5 percent increase). We have also made effective use of other time references by mentioning specific events such as Christmas (e.g. “on Christmas Day”, 13 percent increase) and St Nicholas’ Day (4 percent increase), and by stating the start of the fundraising campaign (“Our fundraising campaign starts today”, 15 percent increase).

Visibility

[edit]In addition to a convincing message, the visibility of the fundraising appeal is of vital importance. Where is the ideal place for a banner? What should it look like? What factors make it more likely to grab readers’ attention? Visual elements should be used in a way that does not compromise the overall design of Wikipedia. The interface of the German-speaking Wikipedia is generally very text-heavy and quite unobtrusive in terms of its design. Banners with overelaborate designs would likely be deemed not to fit in with the accustomed look of the Wikipedia pages and would thus not be taken seriously. But what is an appropriate design for a banner that attracts sufficient attention without interfering with the overall look of the page?

First of all, our banners need to be seen. We have given great thought to the question of when a banner should be displayed. Based on the assumption that users initially just want to search for information and are not receptive to further messages at that stage, we have conducted alone 9 tests on the ideal time delay before a banner appears. The result: the ideal time for the banner to appear is 7.5 seconds after the page has loaded. This enabled us to increase our donation rate per page view by 11 percent. To ensure that Wikipedia content is not covered up because of the time delay, the banner drops down, with the effect of further grabbing the reader’s attention and leading to a further increase in donations (+22 percent). The banner “sticks” to the top edge of the browser window, or else it would no longer be visible when the reader scrolls down. Test findings showed that we could reach and persuade many more people using this “sticky function” and thus attract up to 128 percent more donations.

Visual emphasis, such as the highlighting of key statements, was also important in getting more people to read the message (+ 46 percent). The highlighting of key points has two effects. Firstly, the main messages stand out and so will certainly be read. Secondly, the highlighting provides an additional visual allure, such as the yellow highlighting in 2014, which starkly contrasted with the blue base color of the banner.

Banner color is another key factor. Dozens of different colors have been tested by Wikimedia Foundation and Wikimedia Deutschland, some of which have resulted in significant increases to the donation rate. However, repeat color tests brought remarkably different results. It must therefore be concluded that a change in color is an important factor but one that is temporary in its impact. A change in color probably works best in re-catching the attention of people who have already read, and presumably overlooked, the banner.

Closer to the reader

[edit]Considering that readers do not visit Wikipedia to donate, it is clear that the donation process needs to be kept as simple as possible. This is something we have concluded from the numerous tests we have conducted in recent years. Previously, we tried to convince people with a personal appeal within the banner. This was on the donation page, however, so it not only required more clicks to make a donation, but readers had to take action by themselves before they could read the message. We later successfully integrated the appeal in a drop down space of the banner. This meant we could persuade readers to donate on the Wikipedia page itself, but that the appeal was still only visible once readers clicked on the banner. During the fundraising campaign in 2013, we took the most important persuasive facts from the personal appeal and included them in the banner itself in order to guarantee maximum visibility of the message. More effective than the personal appeals of the past, this facts banner resulted in an increase in the donation rate of 185 percent. The conclusion: the easier an appeal is to read, the more people read it and the more successful we are in convincing them to donate.

In addition to the location of the appeal message, the question of when the donation process starts is important. In keeping with the message’s move from the donation page to Wikipedia itself, the start of the donation process has also moved closer to the user. By integrating the donation form into the banner we are signaling that the donation process has already begun here and that it will therefore not last that much longer. The increase in the donation rate of 98 percent shows that people prefer the more direct approach of the donation process starting within the banner.

We know from a survey of Wikipedia readers that a large proportion (60 percent) of users who might consider donating would never do so online. Sixty percent of survey participants said that they do not click on banners on the Internet. Furthermore, the traditional bank transfer is still the most common way of donating in Germany. To allow those who would like to donate in principle, but would not do so online, to support us, we also accept donations by bank transfer, of course. In order to make donations speedy and simple, we have integrated the bank details into the banner. If the bank details section were not shown until the donation page, we would probably not be able to reach these people.

Minimizing donation obstacles

[edit]How much do I value a project that I use very often but that is essentially free of charge? This is not a very easy question for donors to answer. With the help of suggested amounts on the donation form and in the text, we attempt to give donors some pointers on how much they might like to donate. We know that the €5 donation is by far the most common. Most people only wish to contribute a small amount. Our message should therefore indicate that any amount is welcome, no matter how small. We do this in a variety of ways.

We offer a choice of seven donation amounts on the form (including an empty field for donors to enter an amount of their choice). Tests from the last years have shown that this is most effective number of amounts and that these specific amounts are the most effective. It is crucial that the suggested amounts are not that high. Therefore, 5, 15 and 25 Euro are among the seven suggested amounts.People also recognize that €5 is a perfectly acceptable amount to give. Showing readers that the average donation is €20 is a second reference point. Then the third pointer – the magic words, which tests revealed to be the most convincing of all of our fundraising appeals: “If every reader gave just a small amount, our fundraiser would be over in an hour.” This effective fundraising slogan was previously displayed alone in the banner, but it is now imbedded in the facts banner. The power of this statement is its simplicity and plausibility. Everyone only has to contribute a small amount; we’re not talking about a lot of money – it just needs everyone, or at least very many people, to contribute. These three donation pointers convey the idea that everyone can give something back to Wikipedia at very little effort and cost. The obstacle to donating is thus very low.

One way of minimizing donation obstacles is to accommodate donors’ data protection needs. For several years it has been possible to donate without entering address information (with the exception of SEPA direct debit donations). We simply require the donor’s name in order to clearly identify the donation. Data protection is becoming an ever more important issue for our donors at a time when many people, especially in Germany, are skeptical about entering their personal information on the Internet. The table below shows that the proportion of the total donations that come from “anonymous” donors has increased significantly.

Proportion of “anonymous” donations in the last three fundraising campaigns

| Campaign | Total No. of donations |

No. of anonymous donations |

Anonymous donations as a percentage |

| 2012 | 184.919 | 25.382 | 13,72 % |

| 2013 | 244.652 | 43.303 | 17,69 % |

| 2014 | 289.023 | 86.809 | 30,03 % |

Campaigning

[edit]One very successful move in recent years has been to integrate a donation barometer into the banner at the end of the campaign – a visual indication showing the progress of donations in the form of a pressure gauge. The benefits of this are manifold. The barometer allows us to openly present our donation target and to show readers the number of days remaining and the amount still to be raised in donations. This has always had the effect of increasing readers’ willingness to donate and thus push us to the target. In the run-up to the 2014 fundraising campaign we asked ourselves the following question: Would the donation barometer also be effective at the start of the campaign? And if it was so effective to display the amount still required from donations and the number of days remaining, could we also include other campaign-related information in the banner to achieve a similarly positive effect?

The fundraising barometer has a double impact. Firstly, the fact that it is animated makes it stand out visually and get readers’ attention, making the banner itself more visible. Secondly, the barometer provides important information that, alongside the text in the banner, serves to persuade the reader to donate. By publishing the fundraising target, we are fulfilling the need for information that many German readers have. This is a desire that has been frequently expressed in our correspondence with donors. In displaying the remaining days and the amount still to be raised, we give potential donors an incentive to act within a certain time frame. Precisely that may prove difficult at the start of a campaign, as the remaining time will feel very long. Thanks to our A/B testing, however, we have been able to conclude that this concern is unfounded and that displaying the fundraising barometer at the start of the campaign is in fact very successful (32 percent increase).

Another aspect of our campaigning also had a surprising, positive effect. It is generally assumed that people copy the behavior of others and like to feel part of a group (the principle of “social proof”). People are also more willing to commit to something that other people have already committed to. In the context of our campaign, we translated this as: “Our fundraising appeal is displayed over X million times a day. X hundred thousand people have already donated.” We then tested what would happen if we got rid of “already” and replaced it with “only.” The result was astonishing. Contrary to the principle of social proof, the second variation resulted in an increase in the donation rate of 22 percent. What could this be down to? Here, the word “only” refers to the huge discrepancy between the many millions of people who have seen the banner and the very small proportion of those who have donated. This is highlighted as a problem. The message that such a small number of people have donated pulls readers out of their comfort zone, in which it’s always other people who donate to Wikipedia. This serves as a further incentive to act, on top of the persuasive content of the banner.

Additional elements are added to the banner where appropriate to strengthen the campaigning message. Statements such as “Once a year we ask for your support,” “Now we are asking you in Germany to help out,” and “If every reader gave just a small amount, our fundraiser would be over in an hour.” reinforce the idea that readers should pledge their support to Wikipedia now, this moment. The scope for donating is significantly increased through our campaigning efforts.

During our campaign we achieved one of our few test successes on the donation page. In the past, only very few tests on the content of the donation page have had a lasting positive effect on the donation rate. We have since learned that most people who are considering donating make the decision as to whether to do so upon reading the banner. But in addition to attracting donations, it is also important for us to actively inform people about our work and to be able to request donations via e-mail. For the 2014 fundraising campaign, we tested several ways of asking the reader for authorization to send them information in the future. Initially, this was in simple terms (“Yes, please send me information”). By constantly changing and improving the text to the final version of “Yes, I would like to know if the fundraising campaign was successful. Please let me know if Wikipedia needs my help,” we were able to increase the frequency of an opt-in by 76 percent and further 142 percent.

The importance of building relationships with donors

[edit]We know that very few Wikipedia readers donate. That’s why it’s all the more important for us as an organization to get existing donors to commit for the long term. This will only work, however, if we understand how we can best convince people to pledge regular support.

Multiple donors

[edit]Once a year we ask for donations on Wikipedia itself. Many donors wait for this annual campaign before they donate. Yet each year we still have to state our case of why donations are necessary. This is important because, first of all, there has been a general decline in donations for non-profit organizations in Germany for years (see Deutscher Spendenrat), and secondly, people now exhibit less loyalty to specific organizations. We, too, have to adapt to these facts when trying to attract donors in Germany. Our Donor Survey 2011 shows that 83.3 percent of Wikipedia donors also support other organizations. We therefore always run the risk of our donors favoring other organizations when they make decisions on whom they wish to pledge their support to. The increasing percentage of repeat donors shown in the table below indicates that we are very successful in convincing donors to continue to support us.

| Year | Total No. of multiple donors |

Total No. of one time donors |

Sum of all | Ratio of multiple donors |

| 2012 | 53.260 | 189.985 | 243.245 | 21,90% |

| 2013 | 95.802 | 237.452 | 333.254 | 28,75% |

| 2014 | 135.228 | 254.153 | 389.381 | 34,73% |

But this positive trend cannot be taken as a given. Just like any organization that relies on donations, we have to work toward ensuring that our donors are satisfied with our mission and the work we do to achieve that mission.

Regular donors

[edit]In addition to maintaining multiple donors, the acquisition of regular donors is one of the most important objectives of the fundraising campaigns. For each payment method (bank transfer, SEPA direct debit, PayPal and credit card) we give the donor the option of setting up a standing order. There is also the option of becoming a member of Wikimedia Deutschland, which entails paying an annual membership fee alongside acquiring other rights and duties. From a financial perspective, these regular membership fees are ultimately the same as the standing order donations. The fundraising messages on our website banner do not explicitly refer to such regular donations or memberships, but the promotion of Wikimedia Deutschland memberships is a key part of other campaigns we work on

In recent years, we have managed to significantly increase the percentage of total funding that can be attributed to regular donations. Five percent of all donations now come from standing orders. The increase in regular donations and memberships is a very positive development for the Wikimedia movement from more than just a financial point of view. It is particularly pleasing, because we assume that our donors feel a close connection to the Wikimedia mission and that they perhaps make other contributions to free knowledge besides supporting us financially.

Mailings

[edit]The pleasing increase in memberships is largely owing to the circulation of mailings. In Germany, and probably worldwide, postal campaigns are the most successful way to attract donations in terms of response. In the past, we sent out very few mailings, as we were always at odds with the idea of an “online organization” raising its funds through postal mailings. But the overriding principle here is that we want to convince donors to support Wikimedia. It’s not down to us to decide whether this is achieved via mailings, an e-mail campaign, or an online banner; it should depend on the donor’s preferences.

Sending donation certificates

In order to encourage commitment to good causes, in recent years legislators have provided strong tax incentives for people to contribute to non-profit organizations. All donations are now tax deductible, provided the tax payer presents a donation certificate to prove the German non-profit status of the donation recipient. This document could be seen as the donors’ “return” on their contribution. Trust in organizations also increases when they have charitable status.

Donation certificates are a key part of fundraising in Germany and are an integral part of the relationships with donors – the majority of donors simply expect to receive one. Most organizations send a donation certificate no matter what the donation sum was, because they can use this opportunity to thank donors in a way that is more personal than via e-mail, for example. It is a way to show the donors they are appreciated and thus increase their sense of loyalty to the organization.

We also send donation certificates, of course. And for good reason: according to our Donor Survey 2013, 60 percent of donors think it is important to receive a certificate. The sending of donation certificates is our largest and most successful mailing – with a steadily increasing volume each year.

In this regard, it must be remembered that official donation certificates cannot be sent via e-mail as yet, a fact that leads to high postage costs. But, as with every fundraising activity, the return on investment should be the decisive factor rather than the costs. The sending of donation certificates has proven to be very successful despite the financial outlay, in particular with regard to the acquisition of new members.

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Ratio ( # / Sum ) | ||||

| Response memberships | 1,53 % (726 / 41.835 €) | 1,33 % (1060 / 51.209 €) | 1,18 % (1302 / 65.734 €) | 1,42 % (3891 / n.a.) |

| Response donations | 0,19 % (91 / 5.031 €) | 0,50 % (385 / 19.944 €) | 0,46 % (512 / 29.644 €) | 0,49 % (1348 / 43.808 €) |

| Response overall | 1,72 % (817 / 46.866 €) | 1,81 % (1445 / 71.153 €) | 1,64 % (1824 / 95.378 €) | 1,91 % (5239 / n.a.) |

| Table of the response quotas of the donation receipt mailings four the last four years. The analysis timeframe is one month to gurantee its comparability. The actual response of each mailing is higher. The response of the mailing 2014 is not finalized. Therefore, we are not able to indicate any revenue at this moment. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Postal campaigns

Postal campaigns have many obvious advantages. The mailings can be personalized, flyers and other supplements can be included, and specific groups can be targeted. Most people also still regard a letter as more important than an e-mail or a banner on a website. The age of recipients also plays an important role here. With an average donor age of 48 (see Donor Survey 2013), Wikimedia Deutschland has very young donors compared to other non-profit organizations. But people of this age are quite used to receiving mail from charitable organizations. So why shouldn’t we send mailings too? The successful mailing of donation certificates has shown that this method of communication works well. One A/B test we conducted using postal mailings and e-mails as the two variables (with identical content) showed a significantly higher response to the letter than to the e-mail. The emailing had a 37,8 % decrease in response compared to the mailing.

Our past experience with mailings is that they generate a greater response during fundraising campaigns. This multi-channel approach was used in the 2014 campaign to reach 100,000 Wikimedia donors. Beforehand, we conducted a detailed target group analysis, an A/B test conception, and the letters were personalized accordingly. The results of the mailing campaign were very satisfying: one third of the respondents did support us with a donation or membership during the fundraiser. This recovered multiple times the amount of the expenses. The figures for the acquisition of new members were especially pleasing. Through the mailing campaign alone, we were able to persuade 4889 people to commit to support our mission in the long term.

“Renewal” is another important point in this regard – a term we use for contacting donors whose last donation was made a long time ago. Our mailing list also includes donors who did not donate during the 2013 or 2012 fundraising campaigns. This meant that there was a high probability of them also not donating during the 2014 fundraising campaign. There were two important aspects we needed to consider in our renewal attempts: firstly, we decided that letters were more likely to grab the attention of this target group and would have a higher likelihood of convincing them to donate than a campaign banner on Wikipedia; secondly, the wording of the letter had to be highly personalized and directly reference the previous donation. As the graph indicates, we were correct. Of all the donors who responded to the mailing with a donation, 30 percent had not donated during the 2013 campaign.

We are aware, of course, that the effect of the mailings correlates closely with the effect of the fundraising banner, and that it is therefore ultimately impossible to determine which of the two messages was decisive in influencing donors’ actions. What we do know, however, is that far more people have pledged their long-term support thanks to the mailing campaigns. We can also see that the average donation from the mailings of almost €65 is significantly higher than the average online donation, which is around €20. It is clear that even for us as an online organization, a mailing represents a strong communication channel and is very effective in persuading donors to pledge their support. We can also conclude that we need to adapt the type of fundraising to suit the specific donor in order to be successful. Postal campaigns will therefore continue to play an important role in our fundraising in the future.

E-mail campaigns

We have been sending regular e-mails as part of the fundraiser since 2011. All donors who have granted us prior authorization to do so will receive up to four e-mails during the fundraising campaign. The benefits of e-mails are clear to see. They are practically free of charge; we can segment target groups; we can personalize; and, importantly, we can conduct A/B tests. In particular, we test certain subject lines in order to optimize the opening rate, and include fundraising links and text segments. Unfortunately, our A/B tests have not yet been as successful as our banner tests. Significant response differences are rare with e-mails. We were still able to achieve good results, however, as the following table shows.

| Type of e-mail | Number sent donations |

Average opening rate in percentage |

Percentage of e-mails that result in a donation in percentage |

| Fundraiser e-mails | 352.698 | 27,79 % | 10,39 % |

| Payment reminder | 20.444 | 39,08 % | 9,72 % |

The renewal effect applies to e-mails too. During the fundraising campaign we wrote to almost 20,000 people who promised to donate in the past but had not done so. We asked these people what the reason for this was and whether they would like to be part of the current campaign. Almost ten percent of the people we wrote to responded by donating. A polite enquiry is sometimes all it takes.

Fundraising as a service

[edit]The donor is always the focus of fundraising, which is we must identify his or her needs and preferences. There are numerous ways to find out a donor’s needs and preferences. Alongside interviews and surveys, our donor services play an important role here. This is how we find out what is important to our donors and can take note of and act upon our donors’ preferences. The range of different channels allows us to establish a relationship with donors in a variety of ways. Other contributing factors are that we always use the medium (mailing, banner, e-mail) that has the highest power of persuasion for that particular donor, that we thank the donor by sending a donation certificate, that we contact people where appropriate and, most importantly, that we are always available if anyone wants to contact us.

Wikimedia Deutschland guarantees that during the fundraising campaign, which is by far our busiest time of year in terms of people contacting us, a member of our fundraising team will be available at the regular office times to answer queries from donors. We receive hundreds of calls during the campaign weeks and respond to the calls as they come in. And many more people contact us via e-mail. We replied to 5,500 OTRS messages during the last fundraising campaign, a hundred-percent increase on the previous year. In order to develop good relationships with donors, we must also treat fundraising as a customer service. Wikipedia readers don’t generally come into contact with people who represent in some kind of way Wikipedia and can tell them more about it. That’s why it is all the more important that the dialog between Wikimedia and its donors instills faith in the project and the mission. It is therefore essential – not only for ensuring donor loyalty – that we listen to people and respond to every question as far as possible. This is the only way we can build relationships that will bring us long-term support.

Conclusions

[edit]The goal of our fundraising campaigns is to convince Wikipedia readers that our mission is worthy of their support. Since very few people give anything back to Wikipedia in the form of a donation, gratitude is an important motive for donating, although not quite enough for most people. That is why we try to convince people to donate to a project that they can make use of free of charge. This message must be conveyed through our banners and other communication channels. Thanks to our investigations into what makes a successful banner, we can now understand why certain elements of communication have the desired effect. The optimization of our banners will continue to play an important role in reaching fundraising targets in the future. Although e-mail and postal mailings are important factors in the diversification of revenue, a large part of revenue will come via de.wikipedia.org in the years to come. Given the new challenges resulting from an increased use of the mobile version of Wikipedia and the Google Knowledge Graph, we need to place even greater importance on developing good relationships with our donors. The idea that it is much more difficult to acquire a new donor than to keep hold of an existing one also holds true with us. But even the strongest bonds can break. In the coming years we will therefore dedicate more energy to strengthening relationships with our donors and focus more on satisfying their needs and preferences. If we can successfully develop this side of our work, we will be able to continue to meet the financial targets we need in order to keep promoting free knowledge.

Further links

[edit]

Contact

[edit]Till Mletzko, Wikimedia Deutschland

Tobias Schumann, Wikimedia Deutschland