Europeana/1914-18/Wikimedia CH

Overview

[edit]

Switzerland maintained a state of armed neutrality during the First World War. However, with two of the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary) and two of the Entente Powers (France and Italy) all sharing borders and populations with Switzerland, neutrality proved difficult.

During the War, all Swiss troops were deployed in the Jura along the French border over concern that the trench war might spill into Switzerland. Of lesser concern was the Italian border, but troops were also stationed in the Unterengadin region of Graubünden. While the German-speaking majority in Switzerland generally favored the Central Powers, the French- and, later, Italian-speaking populations sided with the Entente Powers, which would cause conflict in 1918.

During the war Switzerland was blockaded by the Allies and therefore suffered some difficulties and some challenges. However, because Switzerland was centrally located, neutral, and generally undamaged, the war allowed the growth of the Swiss banking industry. For the same reasons, Switzerland became a haven for refugees and revolutionaries.

Following the organisation of the army in 1907 and military expansion in 1911, the Swiss Army consisted of about 250'000 men with an additional 200'000 in supporting roles.

Mobilization of troops

[edit]

After the declarations of war in late July 1914, on August 1, 1914 Switzerland mobilized its army; by August 7 the newly appointed general Ulrich Wille had about 220'000 men under his command. By August 11th, Wille had deployed much of the army along the Jura border with France, with smaller units deployed along the eastern and southern borders. This remained unchanged until May 1915 when Italy entered the war on the Entente side, at which point troops were deployed to the Unterengadin valley, Val Müstair, and along the southern border.

Once it became clear that the Allies and the Central Powers would respect Swiss neutrality, the number of troops deployed began to drop. After September 1914, some soldiers were released to return to their farms and to vital industries. By November 1916, the Swiss had only 38'000 men in the army. This number increased during the winter of 1916–17 to over 100'000 as a result of a proposed French attack that would have crossed over to Switzerland. When this attack failed to occur the army began to shrink again. Because of widespread workers' strikes, at the end of the war, the Swiss army had shrunk to only 12'500 men.

During the war, belligerents crossed the Swiss borders about 1'000 times, with some of these incidents occurring around the Dreisprachen Piz or Three Languages Peak (near the Stelvio Pass; the languages being Italian, Romansh and German). Switzerland had an outpost and a hotel (which was destroyed after being used by the Austrians) on the peak. During the war, fierce battles were fought in the ice and snow of the area, with gun fire crossing into Swiss areas at times. The three nations made an agreement not to fire over Swiss territory which jutted out between Austria (to the north) and Italy (to the south). Instead they could fire down the pass, as Swiss territory was around the peak.

Selection of photos from the Swiss Federal Archives

[edit]-

Cavalry in foot combat

-

Car on the farm of the Zeughauses Lyss

-

Partial view of the Zeughauses Lyss with wagons of the Divisionspark 2

-

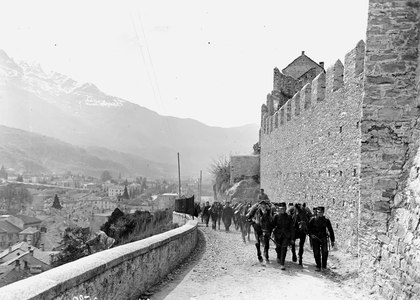

A fringed column of a mountain battalion ascending from Bellinzona

-

Work on the internal equipment of the gas masks, such as the incorporation of the fine wire mesh and lining of the inner walls with sand, etc.

-

Officers during meeting

-

Lathe for shaping the gas mask filters. Right different stages of shaping and finished filters

-

Field artillery on the march

-

Artillery on the march

Switzerland as a refuge for artists and politicians

[edit]

During the fighting, Switzerland became a haven for many politicians, artists, pacifists, and thinkers. Bern, Zürich, and Geneva became centers of debate and discussion. In Zürich two very different anti-war groups would bring lasting changes to the world, the Bolsheviks and the Dadaists[1].

The Bolsheviks, a faction of Russian socialists, centered around Vladimir Lenin. Following the outbreak of the war, Lenin was stunned when the large Social Democratic parties of Europe (at that time predominantly Marxist in orientation) supported their various respective countries' war efforts. Lenin (who was against the war, as he estimated that the peasants and workers were fighting the battle of the bourgeoisie rather than their own) adopted the stance that what he described as an "imperialist war" ought to be turned into a civil war between the classes. He left Austria for neutral Switzerland in 1914 following the outbreak of the war and remained active in Switzerland until 1917. Following the 1917 February Revolution in Russia and the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, he left Switzerland on the sealed train to Petrograd, where he would shortly lead the 1917 October Revolution in Russia.

While the Dada art movement was also an anti-war organization, Dadaists used art to oppose all wars. The founders of the movement had left Germany and Romania to escape the destruction of war. At the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich they put on performances expressing their disgust with the war and with the interests that caused it. By some accounts, Dada coalesced on October 6, 1916 at the cabaret. The artists used abstraction to fight against the social, political, and cultural ideas of that time that they believed had provoked the war. Dadaists viewed abstraction as the result of a lack of planning and logical thought-processes. When World War I ended in 1918, most of the Zürich Dadaists returned to their home countries, and some began Dada activities in other cities.

During the war, Switzerland accepted 68'000 British, French and German wounded prisoners of war for recovery in mountain resorts. The wounded were transferred from prisoner-of-war camps, which were unable to cope with the number of wounded prisoners and sat out the war in Switzerland[2]. The transfer was agreed between the warring powers and organised by the Red Cross.

Selection of photos from the Archives cantonales jurassiennes

[edit]-

"Frontière 1914" by Eugène Cattin

-

Soldiers of the battalion "130", August 1914, by Eugène Cattin

-

Soldiers of the battalion "130", August 1914, by Eugène Cattin

-

Soldiers "Grenze 9.9.1917" by Eugène Cattin

-

"1 homme, 1 femme" by Eugène Cattin

-

Military boat by Eugène Cattin

-

Army policemen and dog by Eugène Cattin

-

Military Officers by Eugène Cattin

-

Soldiers by Eugène Cattin

-

Soldiers by Eugène Cattin

-

Soldiers by Eugène Cattin

-

Soldiers by Eugène Cattin

-

Soldiers including 3 seated and 1 cook by Eugène Cattin

Highlights

[edit]The highlight we would give in this report is based on the answer to a specific question: "What was the technology used to communicate during the conflict? How did the armies communicate with the central commands?".

Communication was very important during the conflict because the central commands had to manage several fronts at once and to move troops from one front to another quickly. The ability to communicate rapidly and reliably made a valuable difference in the conflict.

The topic of communication is strategically connected with our future projects, especially with our collaboration with the Radio Museum hosted in the old building of Radio Monte Ceneri, an important and sometimes crucial radio during World War II.

We will publish here a preview of the work we are doing with this museum. To the question of communication during World War I, this is the answer of the president of the Association of the Radio Museum:

| “ | "Anyone that watched the movie "All Quiet on the Western Front", a terrible testimony from the famous book by Erich Maria Remarque, must have noticed that it is devoid of the presence of radios. At one point, an old gramophone, a legendary and wonderful symbol of the end of the Belle Époque, appears. In the film the horror of the trench war emerges, through the continual fear of death. The entire experience is summoned through the proximity of some comrades in arms and a few heroic leaders, their sole way to receive communication and mutual encouragement. There appear to be no remote connection, no contact with backdrops carrying news about the general situation, the position, the means and intentions of the enemy, even though at the end of the war, some aerial reconnaissance was carried out. Even in the movie "A Farewell to Arms", taken from the book by Ernest Hemingway, there is no record of radiocommunication. Thus was the harsh reality of a war which was largely based on infantry. Aviation is a different topic altogether, with its legendary air battles, as shown by the film "Flyboys", as well as maritime navigation, in which radio telegraphy had a role to play"[3] | ” |

Before World War I

[edit]

Shortly before World War I, several tools were used for long-distance communication: the spark-gap transmitter, and the crystal radio with galena along the Morse alphabet. These were the current technologies in 1912, at the time the Titanic sank. During the Titanic's inaugural journey, on a tragic April 14th, at least seven ships on the route to and from New York had reported to each other, and to the Titanic, the presence of ice floating in the sea. Telegraphic messages were not taken seriously enough. We know how it ended. The wireless officer of the Titanic unfortunately reacted late at night and sent an uninterrupted SOS after the collision with the iceberg. The Carpathia came to rescue the surviving passengers that were found on lifeboats. A telegram was sent to New York: the Titanic had sunk. On large ships on which electricity was available, wireless communication was therefore a reality. This was the state of the art in communication before World War I. A big impulse was provided by Guglielmo Marconi, Nobel for Physics in 1909, who enrolled voluntarily to fight in World War I, becoming a lieutenant in the Italian Navy. Nevertheless, the struggle for survival left little room for science and research. It was found that waves could be propagated over considerable distances in barren areas, but to achieve that, heavy equipment and a lot of electrical power was needed, so radio material was not easy to carry except on adequate means of transport. So there was little to do for the infantry[4].

Naval communication during World War I

[edit]On ships, the use of the radio, better known as "broadcasting", supported by important coastal stations, was similar to its use in civilian navigation. The main difference was that the Morse alphabet was associated with a secret code to cypher/decipher the messages. The naval battle of Jutland (or Skagerrak) is interesting in this context, as the use of the radio transmission had an important role in the battle's outcome. The German Kaiserliche Marine did not know that the Royal Navy had a copy of the codebook from the light cruiser SMS Magdeburg, captured by the Russian navy. The British Admiralty created Room 40 to decypher the German messages. The reliability of these messages was small and an example can be given when the 30th May 1916 the coded signal "31 May G.G.2490" was transmitted to the ships of the fleet to inform them the Skagerrak attack would start on 31th May. The wind was still too strong for the Zeppelins and the final decision was made to use the alternative plan sending a patrol of battlecruisers to Skagerrak. The pre-arranged signal to the waiting submarines was transmitted throughout the day from the E-Dienst radio station in Brugge, and the U-boat tender Arcona anchored at Emden, but only two of the waiting submarines, U-66 and U-32, received the order[5]. In addition, the use of spark transmitters installed on ships was a security liability because due to their directional reception antennas, it was possible to understand from which direction the communicating ships came from. Despite the possibility of knowing in advance the enemy's moves, the Royal Navy suffered considerable losses. We may consider that, without the deciphering of messages and without the use of radio communication, the war would definitely have had a completely different outcome.

Communication in aviation during World War I

[edit]In 1906, Aviation history was marked with the creation of the first Zeppelin. The remarkable size of the cabin immediately made it possible to consider the installation of a radio transmitter. However, practical execution initially generated some fear because the danger in the simultaneous presence of sparks in radio transmitters and hydrogen, which filled the aircraft's huge carrying case. But on 1913, with many precautions, airships were fitted for the first time with radio stations transceivers. Therefore, at the outbreak of the war, the Zeppelin was used as a recognizer at the highest altitude possible since, given their size, shotgun was a serious threat. The high altitudes reachable by these airships gave them their most important advantage: the possibility to transmit via radio at distances up to 300 km, thus reaching the command posts of the artillery, which had the most devastating weapon, to give them the position of enemy lines. This allowed to adjust and correct the shots. Even some planes (Albatros), equipped with spark-ignited radios, were used for this purpose, however, it was not conceivable for a pilot to communicate, as they were overwhelmed by the noise of their engines. Airships and aircrafts, whether explorers or bombers, were a major threat to the troops in the trenches, who were only safe under rain and fog, always the best time for the infantry. The need to eradicate the source of the signal for radio communication was a strong boost to build new type of armed aircraft (i.e. the fighter aircraft like the French Nieuport or the German Fokker)[6].

Communication of the infantry during World War I

[edit]Considering the size of radio equipment at the time, and the unreliability of the other equipment, how did infantry communicate over longer distances? Communication relied on a more traditional method: homing pigeon. We have some material from the Swiss Federal Archives representing this use by the Swiss Army.

-

Dispatching a message by homing pigeon

-

A mobile station wagon for homing pigeons

-

A covered mobile station wagon for homing pigeons

-

A mobile station wagon occupied by homing pigeons

-

Drawing of a homing pigeons

-

Each pigeon has its own place in the wagon

-

The patrol basket with pigeons for cyclists and mountain groups

-

A cyclist's patrol with homing pigeons on its back

-

Homing pigeons are released

-

Homing pigeons and their supervisors

List of projects

[edit]- First World War Switzerland - Swiss Federal Archives (containg a section dedicated to World war I preserved by the Swiss Federal Archives)

- portraits of scientists and mathematicians (containing portraits of scientists and mathematicians lived during World War I preserved by the ETH Library of Zürich)

- Swiss Foundation Public Domain (containg media and covers published during World War I)

- Aerial photographs by Eduard Spelterini takes between 1893 and 1923 (preserved by the Swiss National Library)

- Archives cantonales jurassiennes (containing a section of photos by Eugène Cattin with images of World War I preserved by the Archives cantonales jurassiennes)

- Museo della radio Monte Ceneri (containing material of the Museo della radio Monte Ceneri)

References

[edit]Links

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ↑ La Suisse joue parmi les nations le rôle du bon samaritain - Europeana collection

- ↑ British soldiers interned in Switzerland - Europeana collection

- ↑ This an excerpt of the research of Renato Ramazzina, president of the Association of the Radio Museum, based on the material of the archive and of the library of the museum

- ↑ This is a re-adaptation of the same research of Renato Ramazzina, president of the Association of the Museum of the Radio, based on the material of the archive and of the library of the museum

- ↑ Battle of Jutland

- ↑ This is a re-adaptation of the same research of Renato Ramazzina, president of the Association of the Museum of the Radio, based on the material of the archive and of the library of the museum